Things here below … serve those above; and those celestial in turn, from their divine natures impart to us a certain virtue bringing about the generation of corruptible things within a regular and continuous order, and their decay.”

— Giambattista della Porta, Magia Naturalis, 1558

Between 1346 and 1353 the Black Death swept through Europe, killing perhaps half of the continent’s population. In 1348, France’s King Philip VI commanded a team from the medical faculty of the University of Paris to uncover the origin of the plague. Their conclusion? The plague was caused by the triple conjunction of Mars, Jupiter and Saturn in the sign of Aquarius on March 28, 1345. In their findings, the warm, humid nature of Jupiter drew evil vapors from the earth and its oceans, while the excessive heat of Mars stirred up choler and wars, especially when it transited through Leo in 1347-48, forming a conjunction with the North Node and opposing Jupiter.

This report begs a number of key questions about the medieval worldview. First, why were physicians presenting astronomical phenomena as the root of earthly events? Second, how had the practice of astrology returned to Europe so long after the fall of the Western Roman Empire? By the time of the Black Death, the classical science of astrology had been reintegrated into the daily lives of Europeans, and was seen as complementing, rather than contradicting, orthodox Christian theology. As the Renaissance — “the rebirth of the human spirit” — took off in the Latin West, inspired by the rediscovery of classical forms of learning, the study of the stars would reach new heights. However, the “queen of the sciences” would eventually play a part in its own decline; the development of empiricism and rationalism, coupled with advances in technology, would eventually provide leading thinkers with findings that would change how humans saw themselves in the universe.

The Great Translation Project

While early Christendom sought to distance itself from its pagan past, Hellenistic sciences — astrology included — largely died out in Europe. However, they were wholeheartedly adopted, and in many ways improved upon, in the Muslim world. Western Europe’s closest neighbor, the Umayyad Caliphate in Spain, would become the stepping stone for these forgotten sciences to re-enter Europe, carried in large part by the network of Jewish intellectuals that criscrossed the Mediterranean world.

One exemplar of this network was Ibn Ezra, a Jewish intellectual born in Tudela, Spain, in the 11th century. He traveled widely, reaching as far as Baghdad, and produced works of mathematics, poetry and astrology alongside biblical commentary. Notably, he composed his first text on astrology in Italy, and went on to write several astrological texts encompassing natal, electional, mundane and horary techniques when in Beziers, France around 1150.

The Reconquista accelerated the transit of ancient texts and knowledge from Islamicate Spain into Latin Europe. The fall of Toledo in 1085, for example, opened up Western Europe’s greatest libraries to Christian scholars. The years that followed saw the undertaking of a massive translation project, in which Arab, Jewish and Christian scholars worked to translate Hellenistic texts from Arabic into Latin. European intellectuals such as Adelard of Bath, John of Seville and Plato of Tivoli translated works such as Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos and the works of Abu Mashar, which would both become immensely influential in the Latin West. Of the many texts translated, the Toledan tables — drafted in the 1050s by Islamic scholars in Spain and consisting of planetary positions, as well as information on the astrolabe, precession and time-measuring techniques — represented one of the most essential resources for practicing astrologers.

While many important thinkers of the period may have dabbled in — or at least commented on — astrology, the first astrologers we know of by name in the Latin West were Michael Scot and Guido Bonatti, active in the 12th and 13th centuries, respectively. Scot, a Scottish mathematician and scholar, studied in Toledo, where he learned Arabic well enough to translate Ibn Rushd and Ibn Sina into Latin. He served as science advisor and court astrologer to Fredrick II of the Holy Roman Empire, and penned several works on divination and alchemy.

Bonatti, meanwhile, became the most celebrated astrologer of his time, serving Fredrick II as well as several Italian aristocrats and communal governments. He secured immortality by being featured in Dante’s Divine Comedy, where he appeared in the eighth circle of hell, his head fixed on backwards for the sin of practicing astrology. That said, his most famous work, Liber Astronomiae, covers all four branches of astrology and remains a key textbook for traditional astrologers even today.

The Queen of Sciences

Peter Whitfield, in Astrology: A History, notes that “as far as astrology is concerned, the true Renaissance occurred in the late 12th century, with the recovery of the science from Islamic sources.” Renaissance astrology, thus, became an amalgamation of parts. First, the recovery of Hellenistic source techniques gave astrologers access to ancient techniques and philosophies such as Platonism. Additionally, astrological innovations from Islamic sources were widely used, with the theory of the Great Conjunctions one notable example. That said, there was a tendency among Christian astrologers to emphasize Ptolemy as an exemplar of “true” classical astrology, and dismiss techniques such as horary or lots as “Arabic inventions”. The third element, humanism, saw prominent intellectuals use astrology to develop a rational system to comprehend the universe. By the time the Renaissance was in full swing, astrology was widely popular among the continent’s intellectual elite, who provided not only justifications for its coexistence with a Christian worldview, but also used it to support a mechanistic explanation of how God’s will directed earthly events.

Beyond intellectual circles, much as in the Roman Empire astrology became in part a “royal art”, with what it had to say about fate, fortune and mortality of extreme interest to many powerful figures. Many royal courts employed astrologers, but at times casting the wrong chart at the wrong time could have deadly consequences. One notable example is the 15th-century case of Roger Bolingbroke and Thomas Southwell, who produced a horoscope for Eleanor Cobham predicting the death of King Henry VI of England. The pair, along with two others, were accused of conspiring to kill the king with necromancy, and sentenced to death. Bolingbroke was hanged, drawn and quartered, while Southwell died in prison, and the event was immortalized in William Shakespeare’s play Henry VI, Part 2.

Astrology was considered a scholarly discipline well into the 17th century, and was taught in universities throughout Europe. In fact, it was considered an essential part of a classical liberal arts education, which consisted of instruction in the seven fields of grammar, dialectic, rhetoric, music, arithmetic, geometry and astrology. The extent to which astrological symbolism organized Renaissance intellectual life can be seen in the link between the seven liberal arts and the seven traditional planets. Organized in their traditional Ptolemaic order, the planets were thought to each rule a specific field, with grammar associated with the Moon, dialectic with Mercury, and so on, with astrology said to be ruled by Saturn.

Nobles and royalty consulted astrologers on daily matters, not limited to the reading of birth charts. As the practice of astrology became more ubiquitous, even merchants and common folk had a chance to consult astrologers, who provided a number of valuable services at various levels of society. They worked as military or financial advisors, searched for stolen or lost objects, crafted astrological talismans, and elected times for official events or important pursuits.

Perhaps the most pervasive use of astrology was in medicine. European physicians in the late medieval and early Renaissance periods practiced a system of medicine largely guided by the teachings of Hippocrates and Galen integrated with astrological techniques. It involved procedures such as bloodletting, used to balance the proportion of the four humours in the human body — blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm — which in turn were thought to respond to the essential qualities of the planets — hot, cold, dry and wet. Physicians would cast a patient’s natal chart to determine their temperament — that is, which humour or humours dominated in their body — and refer to contemporary transits to explain the onset, cause or treatment of sickness, with special attention paid to the Moon, the most physical of the traditional planets. They would also cast a “decumbiture” chart at the moment of the onset of the sickness — defined as when the patient first took to bed — to help determine possible treatments and outcomes of the sickness.

An additional resource for medieval physicians was the image of the zodiacal man, which first appeared in Manilius’ first-century Astronomicum. A classic example of the microcosm-macrocosm link that Renaissance thinkers saw as an organizing principle of the universe, it linked parts of the body to signs of the zodiac, starting with Aries and the head, and ending with Pisces and the feet. Physicians considered it dangerous to bleed a patient from a body part ruled by the sign the Moon was in; for example, if the Moon was transiting through Gemini, bloodletting from the hands and arms was seen as potentially deadly.

Hermeticism, Humanism and the Occult

This century, like a golden age, has restored to light the liberal arts, which were almost extinct: grammar, poetry, rhetoric, painting, sculpture, architecture, music … this century appears to have perfected astrology.”

— Marsilio Ficino, 1492

During much of the Middle Ages, astrology was thought to work through hidden natural energies, or the manipulations of demons — a view encouraged by a Church that was often eager to malign astrology. However, as European intellectuals gained access to astrological texts, a number of influential figures helped reposition astrology as a natural science, and a system compatible with orthodox Christian theology.

One way that this was achieved was by creating a differentiation between natural and judicial astrology. While it was perfectly acceptable to link the planets and signs to physical matter — things as diverse as metals, internal organs and herbs — the human soul and God’s will were not physical, and were therefore not subject to the influence of the stars. Astrology could thus be used acceptably for a number of practical applications, such as herbalism, but using it for divinatory purposes — that is, attempting to determine an individual’s fate — was frowned upon.

Astrology also provided a rational system of thinking about the universe, presaging the more conventional scientific systems that would eventually supplant it in intellectual life. While it was considered a religious fact that God created the universe, there was some uncertainty as to how said universe was maintained. Astrology provided a useful solution, with the planets serving as intermediaries between the will of God and the progression of sub-lunar events.

This vein of thought was heavily influenced by the reemergence of neo-Platonism and Hermeticism. One key figure in this process was Marsilio Ficino, an Italian priest and scholar chosen by Cosimo de Medici to refound Plato’s Academy in Florence. In addition to translating the works of Plato, he reintroduced Hermeticism to the Latin West. Its central, semi-legendary figure Hermes Trismegistus was seen as foretelling the coming of Christ, and was thus embraced by many European thinkers as the pinnacle of spiritual knowledge.

While he held that by spiritual examination a man can transcend the fate outlined in his natal chart, Ficino was accused of heresy by Pope Innocent VIII for his interest in astrology, though he was eventually acquitted. He saw astrology as representative of the occult workings of nature, and asserted that man, at the center of the cosmos, had the power to elucidate those workings with the power of science. Ironically, it would be this spirit of investigation, inspired by astrology, that would orchestrate the dismantling of the worldview that supported classical astrology.

Beyond the Copernican Revolution

One striking aspect of Renaissance astrology was how widely it was practiced in intellectual circles, to the extent that a number of figures known today for their contributions to other fields were either practicing astrologers or at least familiar with its teachings. One early example is Geoffrey Chaucer, whose literary works present a number of surprisingly sophisticated astrological allegories, suggesting he was familiar with astrological concepts and techniques. In addition to his seminal contributions to English literature, he wrote the first English treatise on the astrolabe.

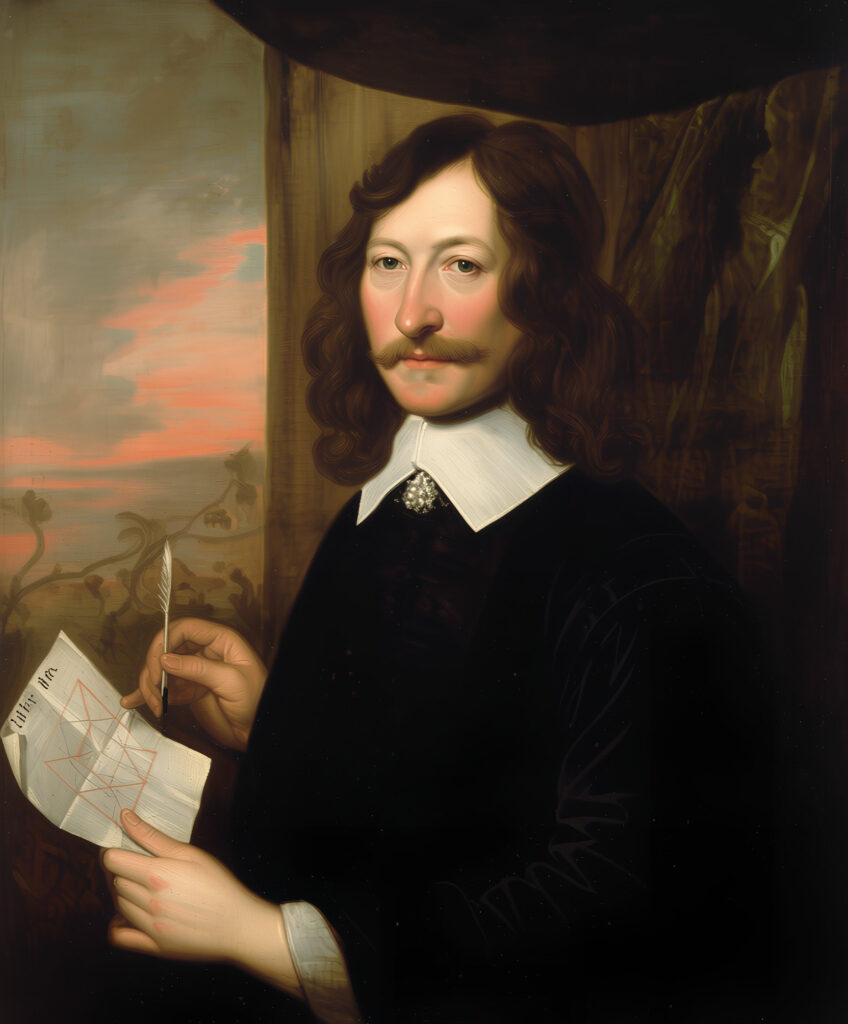

The printing press proliferated an interest in astrology from intellectual circles to the general public. In addition to natal chart collections of famous figures, almanacs with annual predictions were widespread, with the number printed in 17th century England exceeding the number of Bibles. English astrologer William Lilly, for example, published the almanac Merlinus Angliscus with an annual circulation of 30,000. Astrological consultations also became more accessible and widespread, with Lilly reportedly seeing 2,000 clients a year at the height of his career.

Eventually, attempts to rationalize the universe through observation would unravel the Aristotelian physics that formed the bedrock of classical sciences — not just astrology. First, humanity was uprooted from its place at the center of the cosmos when, in the 16th century, Renaissance polymath Nicolaus Copernicus developed a model of the solar system that placed the Sun at its center, rather than the Earth. Then, with the development of superior technology, new advances in observational astronomy began to challenge the idea of a mutable sub-lunar sphere and an immutable, perfect heaven. Galileo Galilei, himself a practicing astrologer, helped disprove this notion by observing sunspots in 1612.

It is important to note that these advancements were initially opposed by Church authorities more fiercely than the leading thinkers of the age, many of whom practiced astrology or parallel occult sciences. Isaac Newton, for example, was infamously fascinated by alchemy, a field that sought to harness planetary influences to transform base metals into gold. Regardless, humanism was supplanted by empiricism, and continuing scientific advancement saw astronomy replace astrology, chemistry replace alchemy and modern medicine replace Galenic medicine as scholarly disciplines over the course of the Enlightenment. Astrology had lost its throne as “the queen of sciences”, and began a gradual decline over the course of the 18th and 19th centuries. When it rose to prominence again near the turn of the 20th century, however, it would owe its rebirth to a reaction against the scientific, materialistic spirit of the modern world, and a new fascination with the nature of the mind and the occult forces of the universe.

References

- History of Astrology in the Renaissance, Christopher Warnock

- Skyscript website – Articles on Morin, Ficino, Bonatti, Schoener, Brahe, Copernicus, John Dee, Gadbury, Lily, Kepler, Forman, Henry II

- Astrology in the Renaissance, by Agostino Dominici

- In Our Time podcast episode on Renaissance Astrology