Shaped by elements of Christian and ancient Greek thought, the Elizabethan worldview envisioned the universe as a balance between heavenly order and sinful chaos, with man the pivotal link in the chain of being.

Category: History

Know more about the history of western traditional astrology from Babylonians to the Arabs.

Abu Ma’shar: Persian Prince of Astrology

Initially a student of the sayings of the Prophet Muhammed, Abu Ma’shar went from prominent skeptic to one of Islam’s greatest Medieval astrologers and was responsible for preserving and synthesizing both Persian and Hellenistic techniques and philosophies.

In the Footsteps of Angels: Medieval Arabic Astrology

As the newly formed Muslim caliphate extended beyond the Arabian Peninsula, it encountered Persian, Hellenistic, and Indian forms of astrology, integrating them into a refined science that would reach its medieval peak in Baghdad, a city whose fortune and fate would be foretold by the stars.

Firmicus Maternus: A skeptic among the stars

A lawyer turned astrologer turned devout Christian, Firmicus Maternus penned the eight-book Mathesis, one of the lengthiest extant works on Hellenistic astrology in Latin, giving sixteen centuries of readers insight into astrological practices during the Roman Empire.

Vettius Valens: Soldier of Fate

Know to the Arabs as “Al-Rumi”, Vettius Valens gained near-mythical status in the East while his fame was largely eclipsed by Ptolemy in the West but his Anthologies remains the most important source contemporary readers have for the foundations and techniques of Hellenistic astrology.

Claudius Ptolemy: A Sage Head in the Clouds

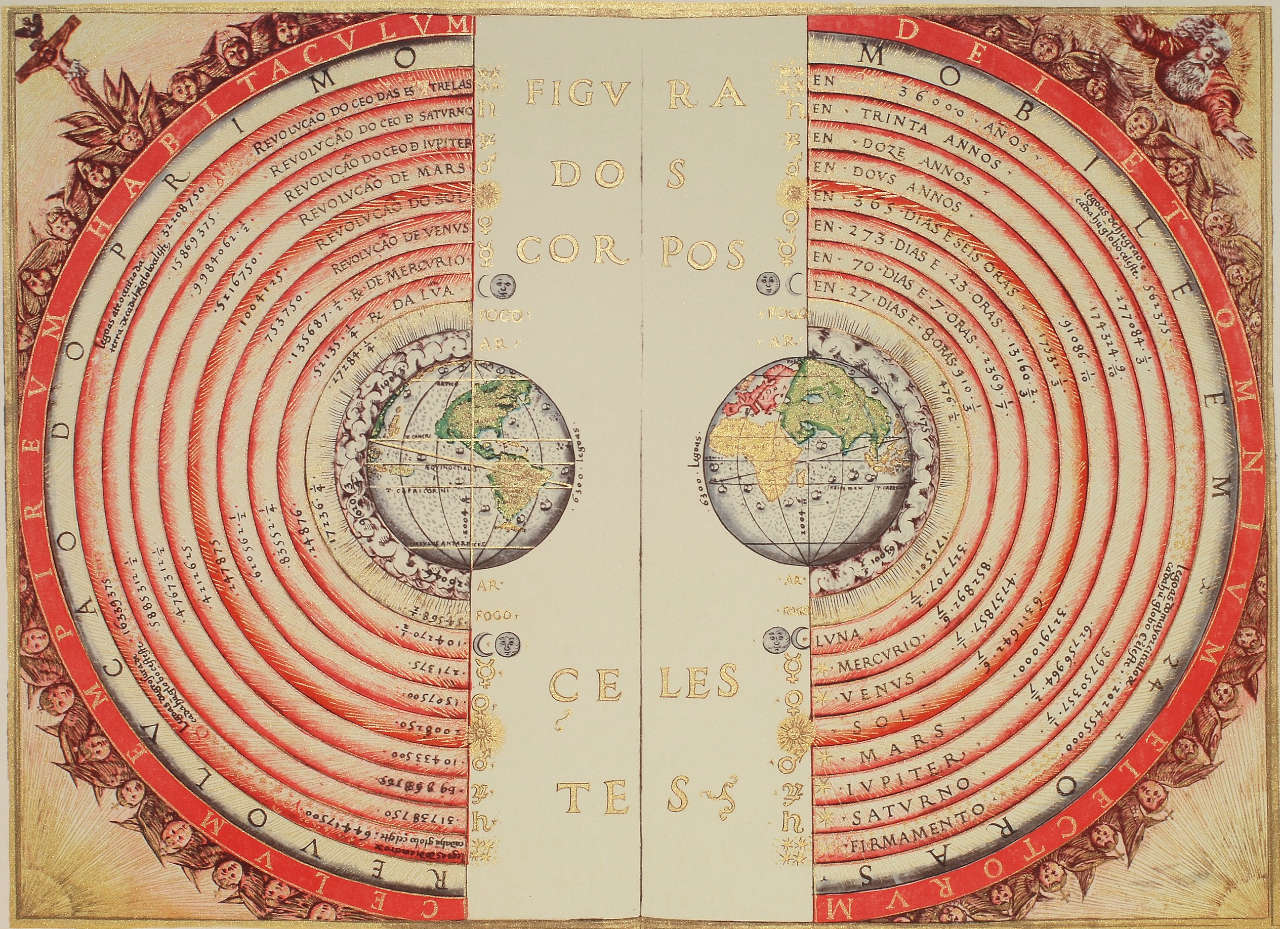

The works of Hellenistic polymath Ptolemy of Alexandria outlined the Western view of the cosmos that would survive until the Copernican revolution and defined the rational-causal view of astrology still largely ascribed to today.

Hellenistic Astrology: Rationalizing Fate

Merging Babylonian star worship with indigenous Egyptian astronomy and Greek mathematics and philosophy, Hellenistic astrologers crafted the fourfold technical structure of astrology that weathered two millennia to survive as the foundational elements of modern astrology today.

The Fault in our Stars: Marcus Manilius and Western Astrology

As the Roman Empire rose, absorbing the trappings of Hellenistic culture, one writer penned the oldest surviving complete treatise on the art of astrology. Part poetics, part mathematics, Manilius’ Astronomica offers a glimpse of the core concepts and Stoic philosophy underlying both Hellenistic astrology and the beginning of modern Western science.

Astrology, Power and the Roman World

In the Roman Empire, knowledge of the stars could get you killed—or help you kill others. Discover how the science of reading the heavens became a powerful political tool in the Roman world.

Heavenly Writings: The Babylonian Origins of Astrology

Over three millennia ago, Mesopotamian scholar-scribes recorded the path of the heavenly bodies across the sky to decipher omens from the gods, laying the foundation for what would become Hellenistic astrology.