Welcome to Lesson 1. You will learn the core building blocks you need to read a natal chart.

We start with the seven classical planets that are visible to the eye: Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, Sun, Venus, Mercury, and Moon. You will learn their names and glyphs. You will also see the lunar nodes (North Node and South Node) and two common Arabic Parts: Part of Fortune and Part of Spirit.

Next, you will meet the 12 signs of the zodiac. You will learn that each sign spans 30 degrees and that planets move through these signs at measurable speeds.

You will explore the traditional worldview that shaped the practice of astrology. We review the Ptolemaic (geocentric) model, the sphere of the fixed stars, and the four elements—fire, earth, air, and water—with their basic qualities.

You will then cast real charts using astro.com with a whole-sign house layout. We will use the birth charts of Charles Dickens and Petrarch as examples. You will learn how to find the Ascendant and Midheaven, turn off the outer planets, select mean nodes, and display the Part of Fortune.

You will identify the chart’s sect. You will decide whether a chart is diurnal (Sun above the horizon) or nocturnal (Sun below the horizon) and understand why that matters.

Finally, you will read an ephemeris to find where the planets are on a given date and to notice direct, retrograde, and station periods.

By the end of this lesson, you will be ready to recognize the main symbols on a chart, set correct software options, and describe what you see with accuracy.

1 Key Foundations

In this section, you will learn the seven classical planets, the twelve signs, the lunar nodes, and two commonly used Arabic Parts. You will also learn how degrees, minutes, and seconds measure positions in the zodiac.

Seven Classical Planets

Traditional astrology uses the seven visible planets. In this course, Sun and Moon are counted as planets.

- Saturn

- Jupiter

- Mars

- Sun

- Venus

- Mercury

- Moon

These bodies were called “wandering stars” because their positions change against the zodiac from day to day.

Lunar Nodes (Not Planets)

The nodes are calculated points where the Moon’s path crosses the ecliptic. They are shown on every birth chart and are important in interpretation.

- North Node (Head of the Dragon)

- South Node (Tail of the Dragon)

Twelve Signs

The zodiac is a 360° circle divided into 12 equal signs of 30° each.

Each degree has 60 minutes (′) and each minute has 60 seconds (″). Planets occupy a specific sign, degree, minute, and second.

Order of the signs:

- Aries

- Taurus

- Gemini

- Cancer

- Leo

- Virgo

- Libra

- Scorpio

- Sagittarius

- Capricorn

- Aquarius

- Pisces

Arabic Parts (Calculated Points)

Arabic Parts are points computed from planetary positions, usually by adding or subtracting zodiacal longitudes with reference to the Ascendant. Two you will use often are:

- Part of Fortune

- Part of Spirit

Related video: Astrology’s Secret Language: A Guide to the Symbols

2 The Traditional Worldview

Of the means of prediction through astronomy, O Syrus, two are the most important and valid. One, which is first both in order and in effectiveness, is that whereby we apprehend the aspects of the movements of sun, moon, and stars in relation to each other and to the earth, as they occur from time to time; the second is that in which by means of the natural character of these aspects themselves we investigate the changes which they bring about in that which they surround.

Ptolemy in Tetrabiblos, trans. Frank Egleston Robbins

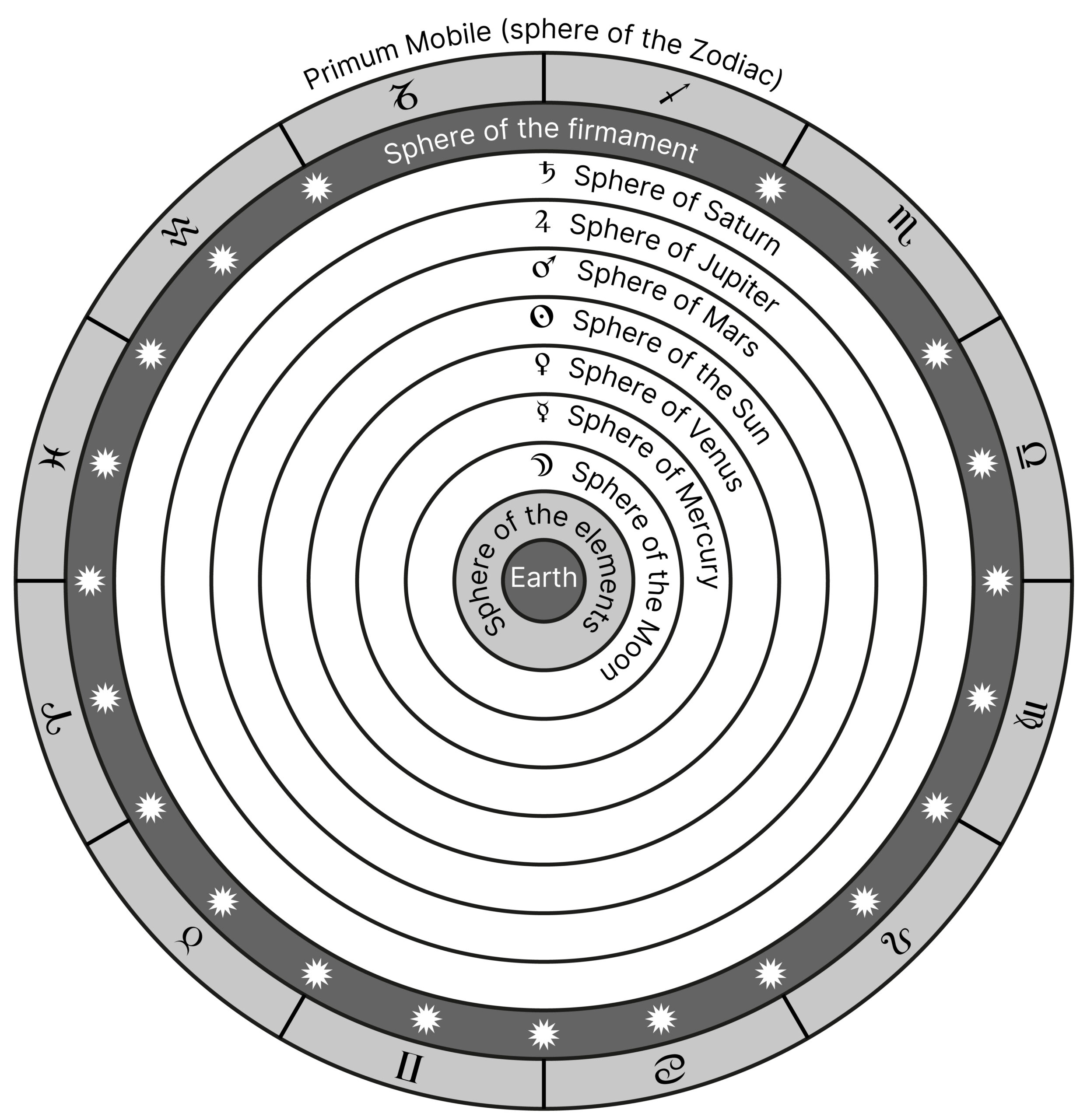

In this section, you will learn the classical picture of the cosmos that shaped traditional astrology: the geocentric model, the sphere of fixed stars, the Primum Mobile, the four elements and their qualities, and the idea of a divinely ordered universe. You will see how this worldview supports the logic of astrological interpretation.

Why worldview matters

Traditional astrology grew from a simple idea: the heavens move in an ordered way, and earthly life reflects that order. When you understand this frame, the techniques you learn later will feel coherent and purposeful.

2.1 The Geocentric (Ptolemaic) Model

In the traditional view of the cosmos, described by the astronomer Claudius Ptolemy, the Earth stood motionless at the center of the universe. Around it were arranged a series of concentric spheres, each carrying one of the seven visible planets. These spheres were ordered according to the planets’ apparent speed in the sky—from the fastest to the slowest:

- Moon

- Mercury

- Venus

- Sun

- Mars

- Jupiter

- Saturn

Together, these formed the planetary spheres of the geocentric or “Earth-centered” universe.

Beyond Saturn lay the eighth sphere, known as the firmament or the sphere of the fixed stars, where the constellations were located. This was the starry background that appeared to rotate nightly around the Earth. Enclosing everything was the ninth sphere, the Primum Mobile or “first mover.” It was believed to impart motion to all the inner spheres and was regarded as the most divine and perfect part of the cosmos.

The fixed stars were considered more divine than the planets because their movement was steady and unchanging. The planets, by contrast, were known as “wandering stars” since they moved along paths that changed daily in relation to the stars behind them. Sometimes, they appeared to move backward—a phenomenon called retrograde motion.

Ancient astronomers explained retrograde motion through epicycles, smaller circular paths attached to the larger planetary spheres. These epicycles allowed astrologers to model the varying speeds and directions of planetary movement while preserving the belief that all heavenly motion was circular, perfect, and orderly.

For the traditional astrologer, this model revealed a structured and purposeful universe. Each sphere had its place and motion, and the movements of the planets within this grand system were seen as reflections of divine intelligence operating through mathematical harmony.

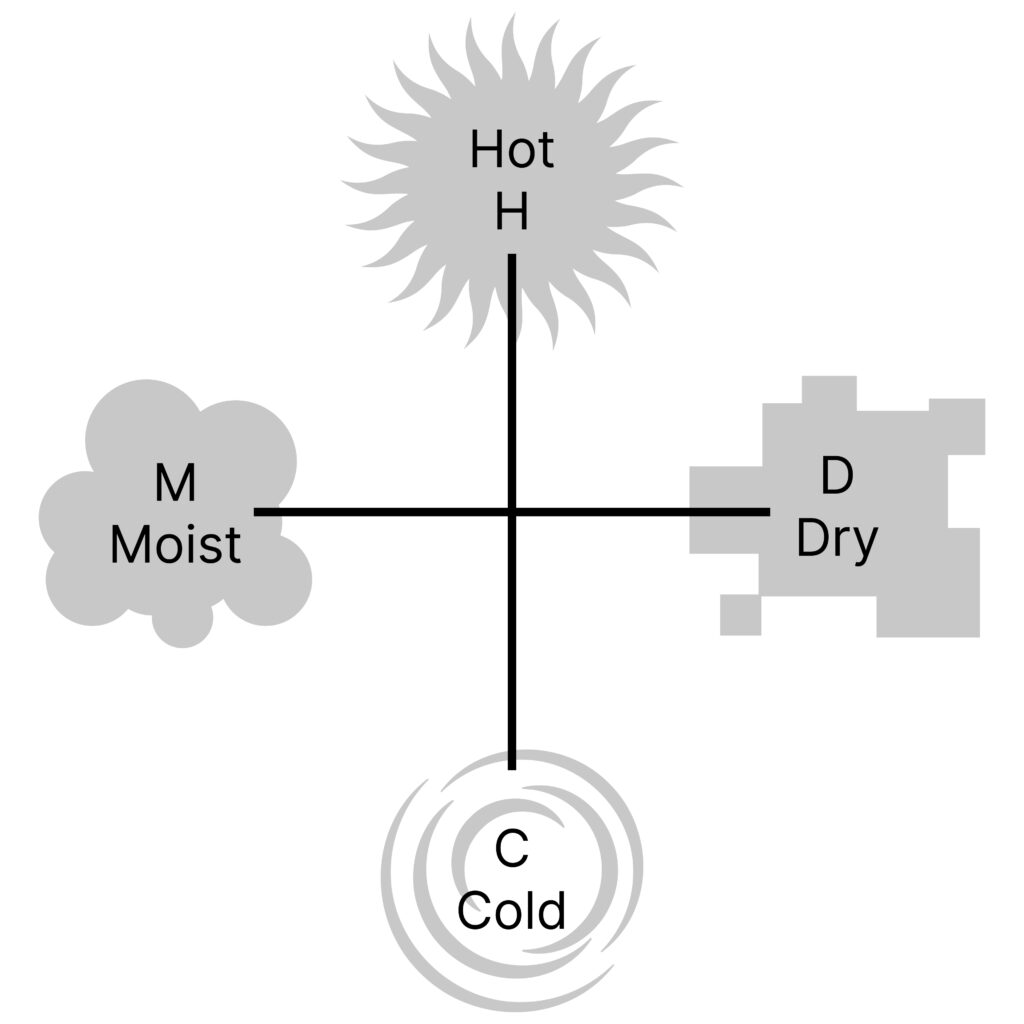

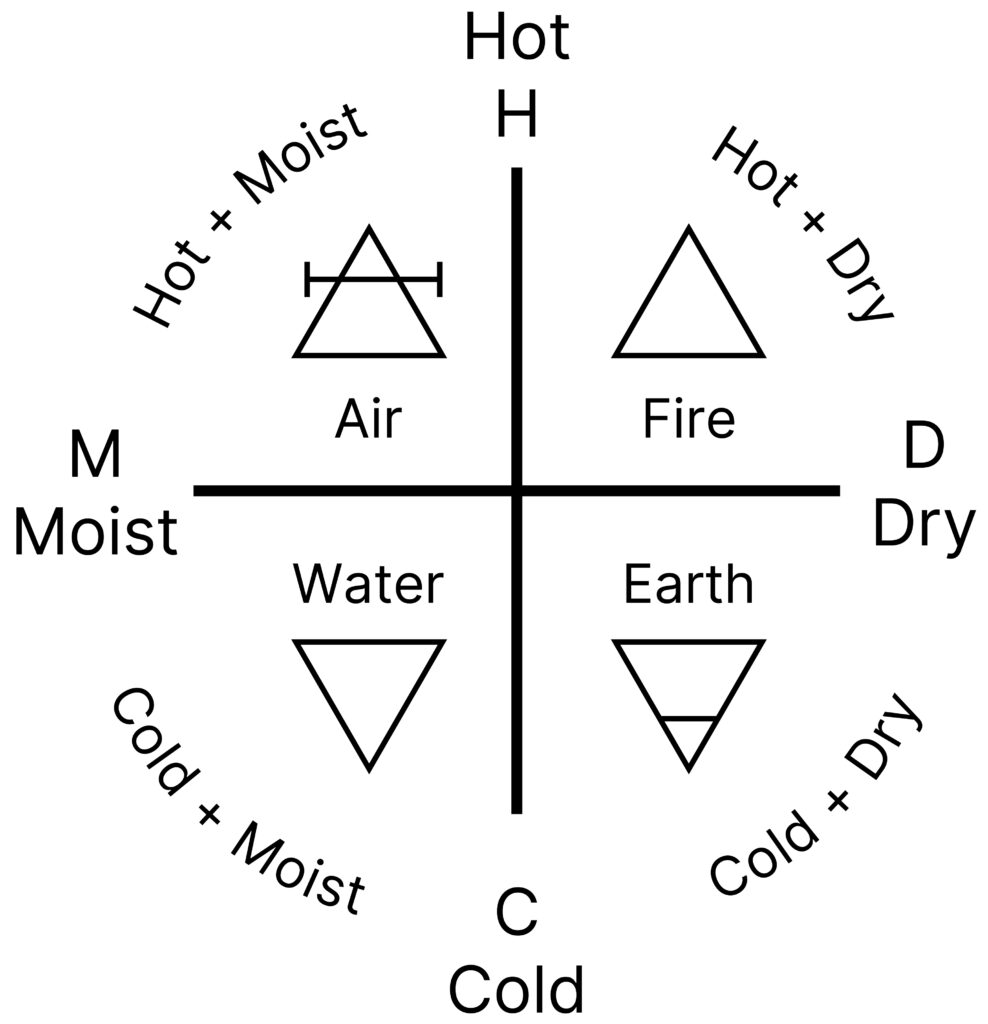

2.2 The Four Elements and Their Qualities

The foundation of classical natural philosophy rests on the four elements—fire, air, water, and earth—and the four primary qualities identified by the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BCE): hot, cold, dry, and moist.

Each element is formed by a unique combination of two of these qualities:

- Fire: hot and dry

- Air: hot and moist

- Water: cold and moist

- Earth: cold and dry

Ancient thinkers believed that everything on Earth was made from these four elements in different proportions. These combinations gave rise to the variety of substances, forms, and living things in the natural world.

Natural Arrangement of the Elements

In the traditional model of the cosmos, the elements were thought to form concentric layers around the Earth:

- Earth, the heaviest element, occupied the center.

- Water surrounded the Earth in the form of seas, rivers, and lakes.

- Air formed the atmosphere above the water.

- Fire, the lightest element, occupied the region nearest to the heavens.

Each element was believed to have a natural motion: earth and water tended to sink toward the center, while air and fire tended to rise. This balance of rising and falling created stability within the natural world.

Transformation and Change

The elements were not fixed but constantly interacted. Under certain conditions, one element could change into another—for example, when heat caused water to evaporate into air. This continuous process of transformation explained growth, decay, and renewal in the world below the Moon.

Although change was ever-present, it followed predictable rhythms that reflected the regular movements of the heavens. This harmony between celestial order and earthly change formed one of the philosophical bases of traditional astrology.

2.3 Order and the Chain of Being

In the traditional worldview, the universe was seen as a vast, ordered hierarchy known as the Chain of Being. At the top was the divine source, followed by the celestial realm of the fixed stars and planets, and finally the sublunar world of Earth, where life was constantly changing and imperfect. The Moon was viewed as the boundary between the unchanging heavens and the mutable world below.

Everything in creation—spiritual or material—had its place in this chain, and all levels were connected. The motion of the heavens was considered perfect, constant, and purposeful. The changes we observe on Earth—birth, growth, decay, and renewal—were thought to reflect that higher order. Astrology arose from this belief: by studying the orderly movement of the planets and stars, we can understand the rhythm of change in human affairs.

During the Renaissance, this classical idea of divine order gained new importance. Thinkers and astrologers such as Ptolemy were studied and respected for showing how celestial movements influence the world below. The Tetrabiblos was valued because it offered a systematic way to interpret the heavens in light of this divine structure.

Renaissance and Elizabethan astrologers believed that fate worked through the predictable cycles of the heavens. Each of the twelve zodiac signs was seen as having unique properties, and the planets moved through them in precise mathematical harmony. What might appear random—shifts in fortune, weather, or temperament—was understood as part of a cosmic pattern ruled by divine law.

How this helps your practice

- You learn to see the birth chart as part of a larger, living order rather than a collection of unrelated symbols.

- You expect cycles and patterns in life because they mirror the ordered movements of the heavens.

- You connect celestial order—planets, signs, and timing—to earthly experiences such as health, vocation, and relationships.

- You develop respect for astrology as both a spiritual and technical art grounded in an ancient understanding of universal harmony.

Related video: Why Traditional Astrology Makes So Much Sense

3 Tropical Zodiac

Since the sun, when he is in Aries, is making his transition to the northern and higher semicircle, and in Libra is passing into the southern and lower one, they have fittingly assigned Aries to him as his exaltation, since there the length of the day and the heating power of his nature begin to increase, and Libra as his depression for the opposite reasons.

Ptolemy in Tetrabiblos, trans. Frank Egleston Robbins

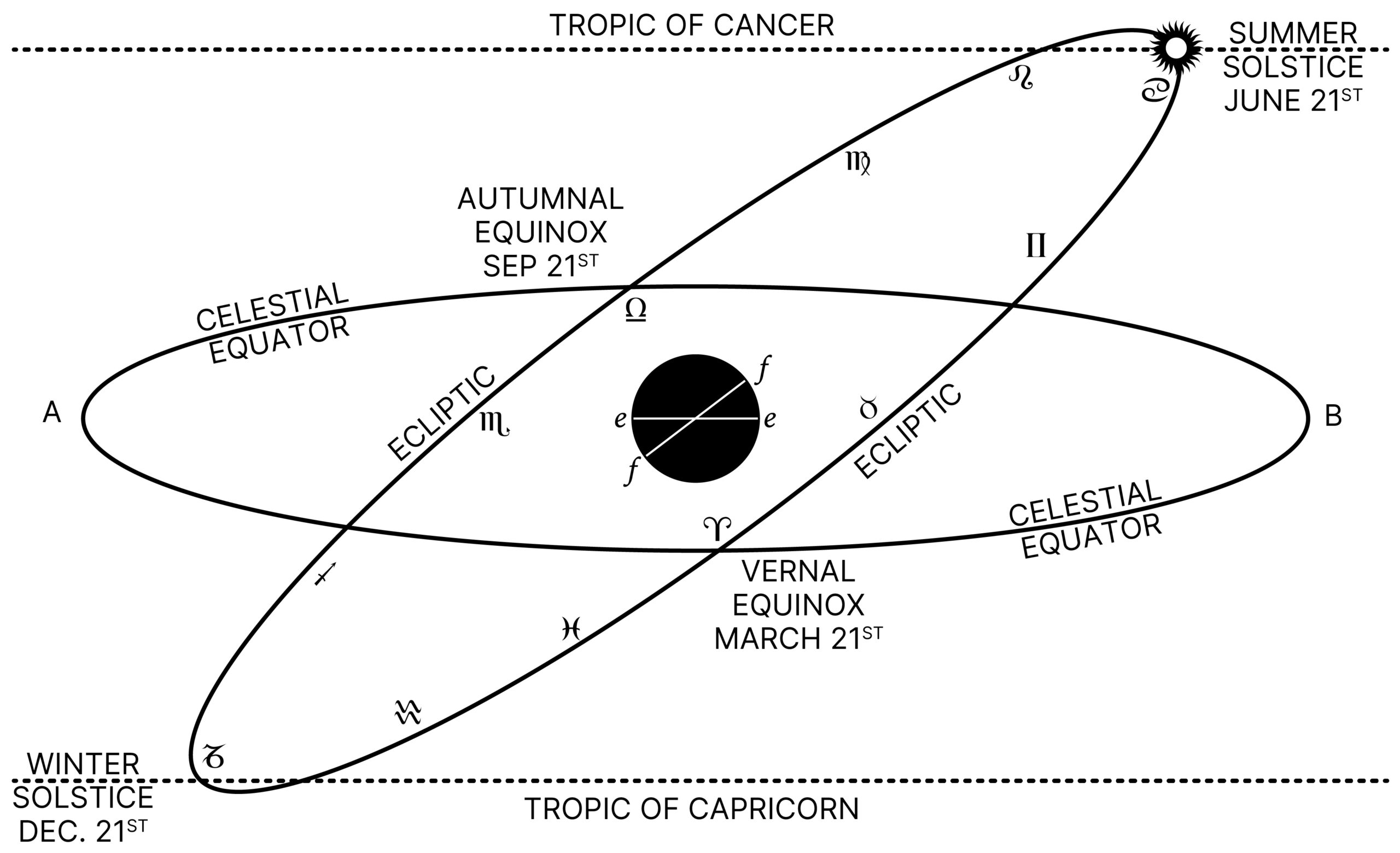

In this section, you learn how the Tropical Zodiac is anchored to Earth’s seasons, not to the star constellations. You will connect the ecliptic, the celestial equator, the equinoxes and solstices, and the four cardinal signs.

Read: Tropical Zodiac (article on satyastrology.com)

Watch: The Tropical Zodiac – Connecting Earth’s Seasons and the Stars

The ecliptic and the celestial equator

- The ecliptic is the apparent path of the Sun (and the path along which the Moon and planets move).

- The celestial equator is Earth’s equator projected into space.

- Because Earth is tilted about 23.44°, the ecliptic is inclined to the celestial equator. They intersect at two points: 0° Aries and 0° Libra (the equinoxes).

What “tropical” means

The Tropical Zodiac is defined by the seasons in the Northern Hemisphere. It divides the ecliptic into 12 signs of 30° each, starting at 0° Aries, the point of the vernal (spring) equinox—when day and night are equal and daylight begins to increase.

The four cardinal points and the seasons

These four points structure the year and anchor the cardinal signs:

- 0° Aries — Vernal equinox (around March 21): day and night are equal; the Sun climbs north; spring begins.

- 0° Cancer — Summer solstice (around June 21): longest day; the Sun reaches its northernmost point.

- 0° Libra — Autumn equinox (around September 21): day and night are equal; the Sun moves south; autumn begins.

- 0° Capricorn — Winter solstice (around December 21): shortest day; the Sun turns to climb north again.

Seasonal progression through the signs

- As the Sun moves through Aries, Taurus, Gemini, days grow longer.

- Near 0° Cancer, daylight peaks (summer solstice). Heat lags and often peaks in Leo.

- From Cancer through Leo to Virgo, the Sun moves south; days begin to shorten.

- At 0° Libra, day and night balance again (autumn equinox). The Sun continues through Libra, Scorpio, Sagittarius.

- At 0° Capricorn, winter begins (winter solstice). The Sun then moves through Capricorn, Aquarius, Pisces, returning to 0° Aries to repeat the cycle.

Tropical vs. constellations

Sign names come from ancient constellations, but in the Tropical system the signs are seasonal segments, not star groups. This is why sign boundaries stay tied to the equinoxes and solstices, even though star positions shift slowly over time.

Classical note

As Ptolemy explained, the Sun’s strength grows at Aries (exaltation) as daylight increases, and declines at Libra (depression) as daylight wanes. This seasonal logic is the backbone of the Tropical Zodiac.

4 Horoscope

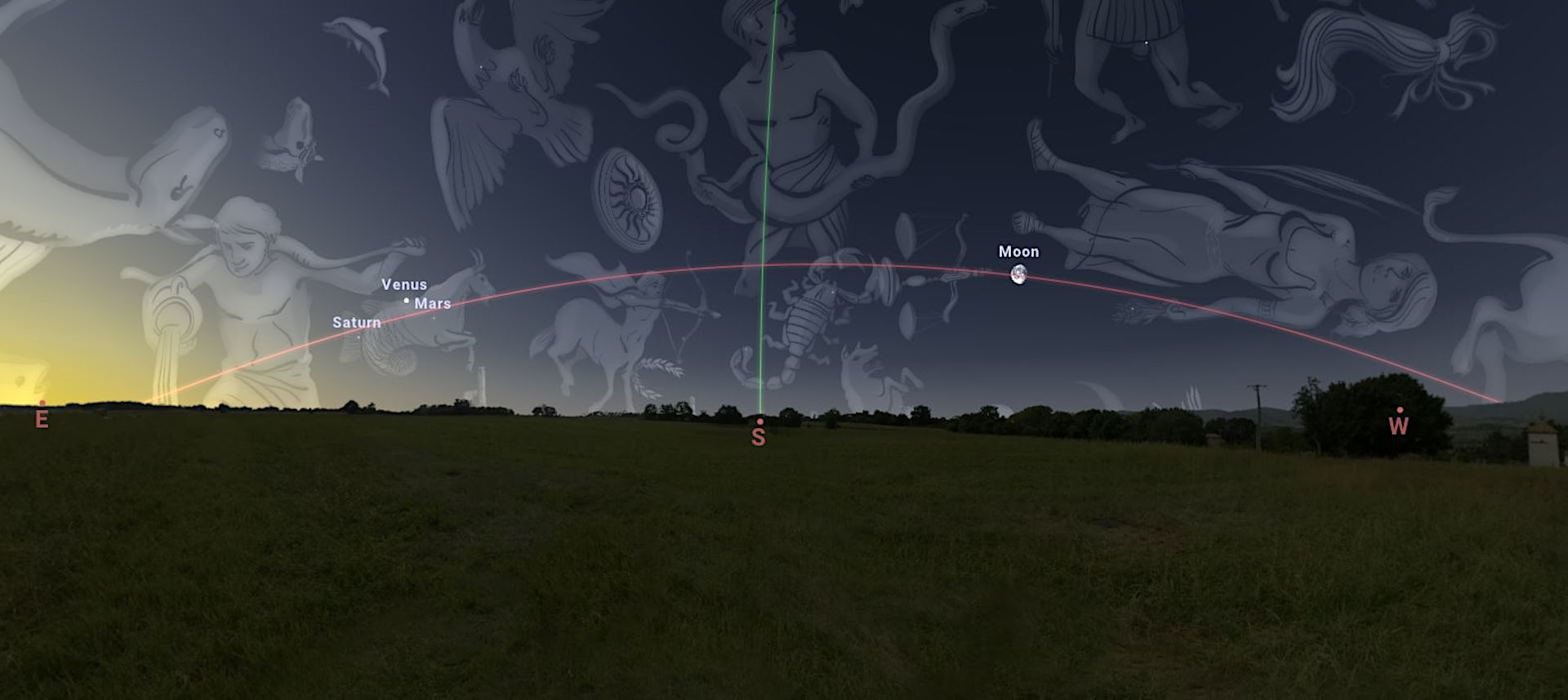

If we looked at the sky just before sunrise when the Sun enters Aries on March 21, 2022, in New York, we should see something similar to the following image (without the constellation art, of course):

Two motions to know

- Primary (diurnal) motion: the sky’s apparent left-to-right rotation due to Earth’s spin. It completes a full 360° turn about once every 24 hours and brings the next sunrise.

- Secondary motion: the planets’ right-to-left drift through the zodiac over days and weeks. The Moon is fastest; Saturn is slowest.

The ecliptic and the horizon

We see that Venus, Mars, and Saturn are visible in the eastern sky and the Moon is visible in the west. The Sun is below the horizon but the day is slowly dawning.

- The ecliptic is the red arc in the diagram—the path where you find the Sun and planets.

- The horizon is the line separating the sky from Earth. Where the ecliptic meets the eastern horizon is the Ascendant (ASC), a point linked with life force and the start of the 1st house. The point exactly opposite is the Descendant (DSC).

The Meridian and the Midheaven

- The Meridian (drawn in green) is the great circle that passes through the celestial poles.

- Where the Meridian crosses the ecliptic is the Midheaven (MC). It marks the degree culminating overhead and, in quadrant systems, sets the 10th-house cusp. MC is associated with public life, career, and reputation.

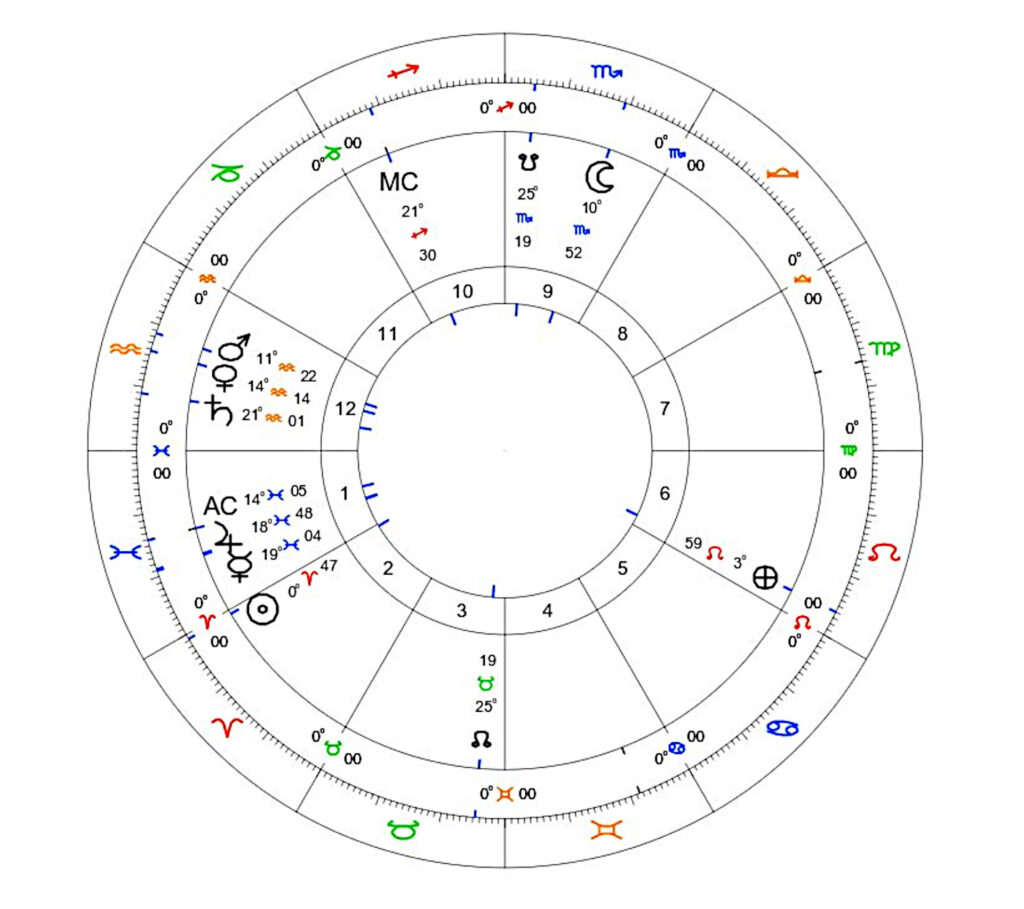

The Astrology Chart

A map of the visible sky along with the planets below the horizon can be plotted in the circle of the zodiac and that is the astrology chart of this moment.

- ASC: Pisces 14°05′ (the horizon line runs from the 1st to the 7th houses).

- Sun: 0°47′ Aries, below the horizon

- Visible planets: Venus, Mars, Saturn rising in the east; Moon setting in the west.

- MC: in Sagittarius (culminating above the Earth).

- Displayed in whole-sign houses: each house equals a full sign starting from the Ascendant’s sign (Pisces = 1st … Aquarius = 12th).

(Note: In whole-sign houses, the ASC degree can fall anywhere within the 1st sign/house. The DSC is 180° from the ASC and together they mark the horizon.)

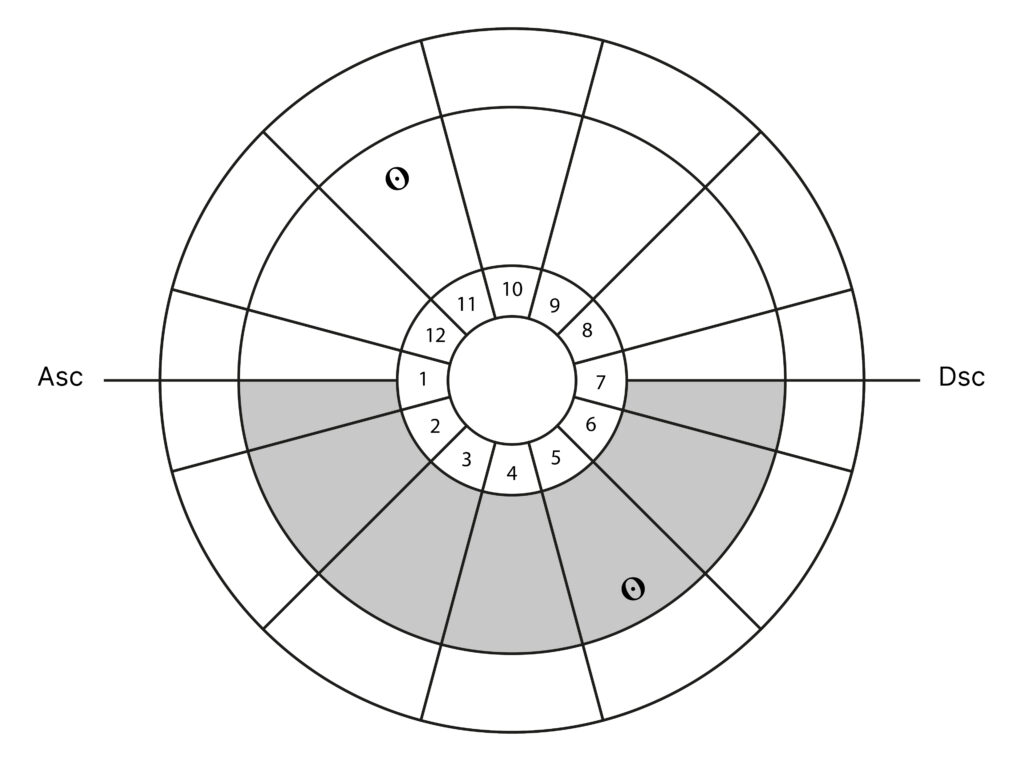

4.1 Sect of the Chart

You will learn how to identify whether a chart is diurnal (day) or nocturnal (night) by checking the Sun’s position relative to the horizon. This is the first step in sect analysis in traditional astrology.

What sect means

In traditional astrology, sect divides charts into two categories:

- Diurnal sect: the chart is a day chart.

- Nocturnal sect: the chart is a night chart.

Sect matters because some planets are considered stronger or more supportive by day, and others by night. You will use the chart’s sect later when you judge planetary condition.

How to determine sect (step by step)

- Find the horizon line: draw an imaginary line from the Ascendant (ASC) to the Descendant (DSC).

- Locate the Sun: see whether the Sun is above or below this horizon line.

- Decide the sect:

- If the Sun is above the horizon → Diurnal chart.

- If the Sun is below the horizon → Nocturnal chart.

- If the Sun is above the horizon → Diurnal chart.

Practical note (twilight cases)

If the Sun is below the horizon but very close to the Ascendant you might need to consider civil twilight to judge if the chart is diurnal or nocturnal; morning civil twilight begins when the Sun is around 6 degrees below the horizon

Example reminder

In the March 21, 2022, pre-sunrise New York chart shown earlier, the Sun is below the horizon, so the chart is nocturnal.

4.2 Horoscope Calculation — Charles Dickens

You will cast a whole-sign natal chart for Charles Dickens and record basic placements. Follow the step-by-step setup in our chart-calculation guides.

Read first:

- How to calculate a traditional chart with astro.com

- How to calculate a traditional chart with astro-seek.com

Required chart settings (summary checklist)

- House system: Whole Sign

- Nodes: Mean Nodes

- Outer planets: off (Uranus, Neptune, Pluto)

- Part of Fortune: display on

- Aspect lines: optional (none for this lesson)

Data to use (from Astrodatabank)

- Charles Dickens: Feb 7, 1812, 7:50 PM, Portsmouth, England (Rodden A)

What to capture (for your notes)

- Ascendant sign and degree

- Midheaven sign and degree

- Sun’s position relative to the horizon (to determine sect)

- Each planet’s sign and whole-sign house

Sect result (for check): Dickens’ Sun is below the horizon → Nocturnal chart.

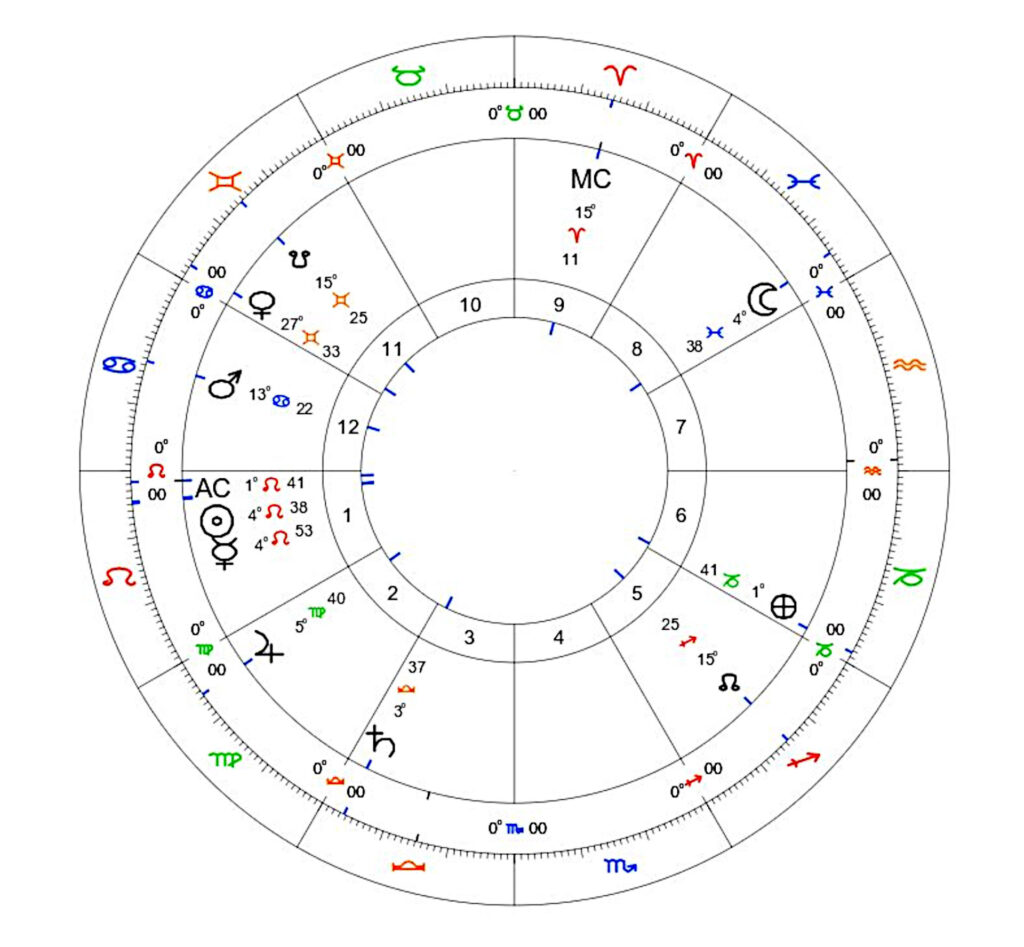

4.3 Horoscope Calculation — Petrarch

You will cast a whole-sign natal chart for Petrarch, noting that his birth date uses the Julian calendar. Use our chart-calculation guides and the platform’s Julian-date entry method.

Data to use (from Astrodatabank)

- Petrarch:July 20, 1304 (Julian), 4:33 AM, Arezzo, Italy (Rodden B)

On astro.com, enter the date in Julian format per the site guide

What to capture (for your notes)

- Ascendant sign and degree

- Midheaven sign and degree

- Sun’s position relative to the horizon (sect)

- Each planet’s sign and whole-sign house (to be tabulated in Section 4.5)

Sect note (edge case): Petrarch’s Sun is below the horizon but within about 6°; for teaching purposes we treat this as diurnal (civil-twilight consideration).

4.4 Planets in Sign and House

You will practice reading a completed chart by listing each planet or point with its sign–degree and whole-sign house. This builds accuracy in chart notation.Record the zodiacal longitude (sign and degree) and the whole-sign house for each planet and key point. Use the charts you generated earlier.

Charles Dickens — placements (whole-sign houses)

| Planet or point | Zodiacal Longitude | Whole SignHouse |

| Ascendant | 18 degrees 50 minutes Virgo | 1 |

| Midheaven | 15 degrees 32 minutes Gemini | 10 |

| Saturn | 4 degrees 22 minutes Capricorn | 5 |

| Jupiter | 26 degrees 29 minutes Gemini | 10 |

| Mars | 7 degrees 33 minutes Aries | 8 |

| Sun | 17 degrees 58 minutes Aquarius | 6 |

| Venus | 16 degrees 16 minutes Pisces | 7 |

| Mercury | 22 degrees 10 minutes Capricorn | 5 |

| Moon | 12 degrees 36 minutes Sagittarius | 4 |

| North Node | 9 degrees 12 minutes Virgo | 1 |

| South Node | 9 degrees 12 minutes Pisces | 7 |

| Part of Fortune | 24 degrees 11 minutes Scorpio | 3 |

Note: In whole-sign houses, the Ascendant’s sign defines the 1st house. The degree of the Ascendant can fall anywhere within that sign.

Petrarch — placements (whole-sign houses)

For the chart of Petrarch, the following is the zodiacal longitude of each planet, ASC, MC, the nodes, and Part of Fortune, along with the whole sign house location:

| Planet or point | Zodiacal Longitude | Whole SignHouse |

| Ascendant | 1 degrees 41 minutes Leo | 1 |

| Midheaven | 15 degrees 11 minutes Aries | 9 |

| Saturn | 3 degrees 37 minutes Libra | 3 |

| Jupiter | 5 degrees 40 minutes Virgo | 2 |

| Mars | 13 degrees 22 minutes Cancer | 12 |

| Sun | 4 degrees 38 minutes Leo | 1 |

| Venus | 27 degrees 33 minutes Gemini | 11 |

| Mercury | 4 degrees 53 minutes Leo | 1 |

| Moon | 4 degrees 38 minutes Pisces | 8 |

| North Node | 15 degrees 25 minutes Sagittarius | 5 |

| South Node | 15 degrees 25 minutes Gemini | 11 |

| Part of Fortune | 1 degree 41 minutes Capricorn | 6 |

Note: In whole-sign houses the MC can fall in houses other than the 10th (here, the 9th). This is normal and useful in interpretation.

Related video: Your Astrology Birth Chart EXPLAINED

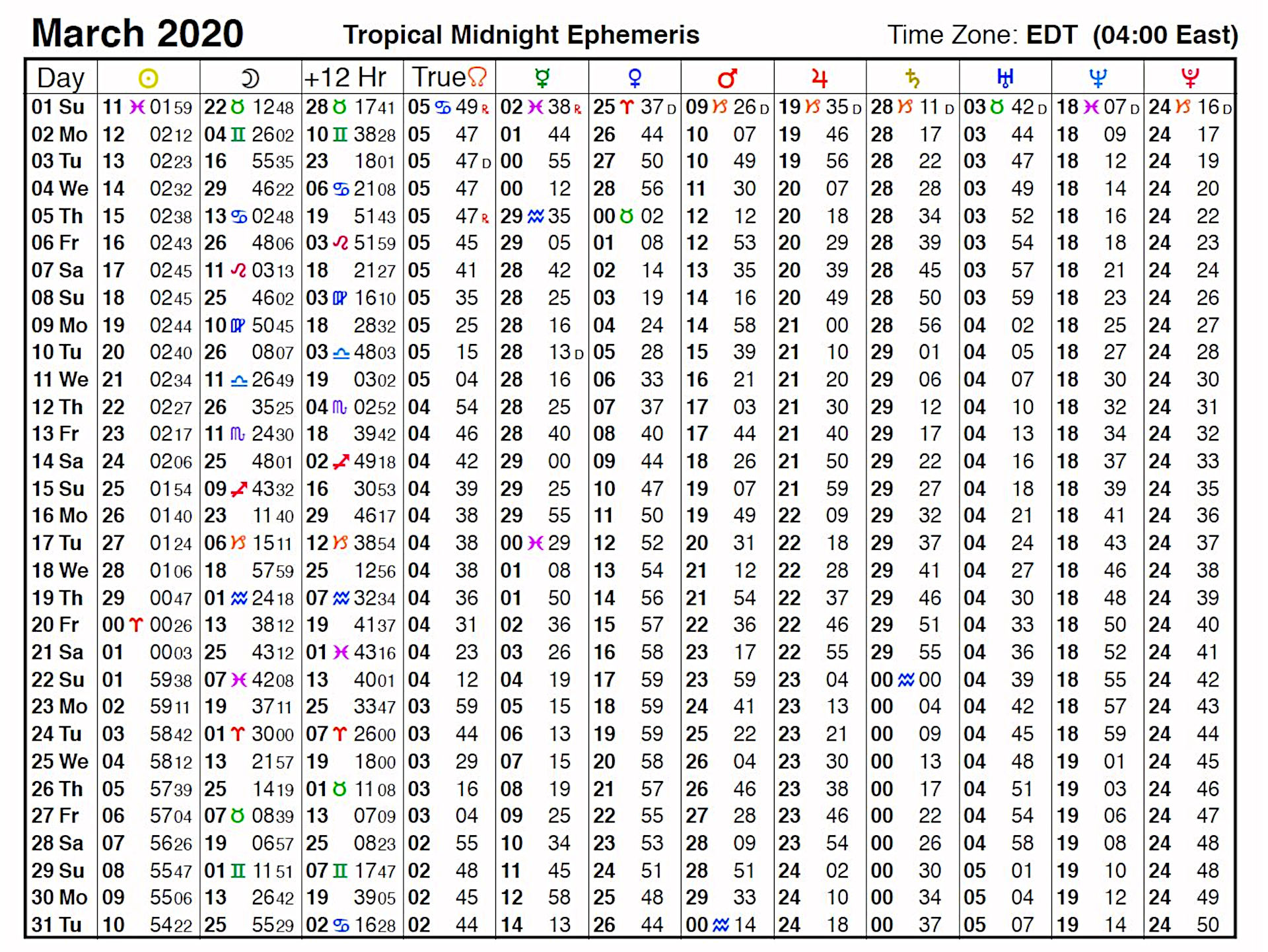

5 Ephemeris

I would have all men well and readily apprehend what precedes, and then they will most easily understand the Ephemeris, which is no other thing than a book containing the true places of the planets, in degrees and minutes, in every of the twelve signs both in longitude and latitude, every day of the year at noon

William Lily, Christian Astrology

You will learn what an ephemeris is, how to read it, and how to use it to track planetary motion (direct, retrograde, stations) around a birth date.

What an ephemeris is

An ephemeris is a table that lists the daily positions of the Sun, Moon, and planets—by sign, degree, and minute (often at a set reference time, such as midnight or noon). As William Lilly put it, it is simply a book that gives you the “true places of the planets.”

What you will see in a monthly table

- Date column: the day of the month.

- Planet columns: Sun through Saturn (and often outer bodies—ignore those for this course).

- Moon columns: two entries are common—midnight and +12 hr (noon)—because the Moon moves quickly.

- Status marks:

- R or Rx = retrograde (apparent backward motion).

- D = direct.

- A small S or a day with the same degree on consecutive entries can mark a station (very slow movement).

- R or Rx = retrograde (apparent backward motion).

Reading a line (worked example)

Above is the ephemeris of March 2020 from https://cafeastrology.com/2020-ephemeris.html. This provides the position of different planets for each day in that month for the eastern time zone, which is four hours behind UTC.

From the March 2020 ephemeris (Eastern Time):

- March 15, 2020 (00:00):

- Sun = 25°01′ Pisces

- Moon = 9°43′ Sagittarius (with a second column showing the noon position)

- Jupiter = 21°59′ Capricorn

- Sun = 25°01′ Pisces

- Mercury shows Rx earlier in the month and turns D on March 10. This is how you spot a retrograde-to-direct change.

What you use the ephemeris for

- Around-birth motion: See if a planet slowed, stationed, or reversed near the birth date.

- Direction of motion: Confirm direct vs retrograde on the day of birth.

- Upcoming aspects/transits: Note when planets will change signs or perfect aspects soon after birth.

- Timing checks: Understand why a planet’s condition (e.g., stationing) might strengthen or weaken its expression in delineation.

Practical tips

- Always note the time standard of the ephemeris (e.g., midnight or noon, and the time zone used).

- For the Moon, use the +12 hr column to see how far it travels within a day.

- For our traditional course settings, ignore Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto.

Free ephemerides: You can download long-range PDF ephemerides (e.g., 5000 BCE–3999 CE) from well-known providers like Astrodienst.

https://www.astro.com/swisseph/swepha_e.htm

Summary

In this first lesson, you learned the foundational structure of traditional natal astrology. You now understand how the visible heavens form the basis for the birth chart and how ancient thinkers organized the cosmos into an ordered, meaningful system.

You explored the seven classical planets, the twelve signs of the zodiac, and key mathematical points such as the lunar nodes and Arabic Parts. You also studied the traditional worldview—the geocentric model, the four elements, and the concept of the chain of being—which together explain how celestial order mirrors life on Earth.

You learned how the Tropical Zodiac is rooted in Earth’s seasons and how the equinoxes and solstices define the cardinal signs. You practiced reading the sky as a chart by identifying the Ascendant, Midheaven, and horizon line, and you determined whether a chart is diurnal or nocturnal through sect analysis.

Using the example charts of Charles Dickens and Petrarch, you calculated whole-sign charts, recorded planetary positions, and classified each chart’s sect. You also learned how to use an ephemeris to find planetary positions, track direct and retrograde motion, and recognize stations.

By the end of Lesson 1, you should be able to:

- Name and identify the seven classical planets and twelve signs.

- Describe the geocentric model and the philosophical order underlying astrology.

- Explain how the Tropical Zodiac is based on the seasons.

- Locate the Ascendant, Midheaven, and horizon line on a chart.

- Determine whether a chart is diurnal or nocturnal.

- Generate a whole-sign natal chart with correct settings.

- Record planetary positions and house placements accurately.

- Read an ephemeris and interpret planetary motion around a birth date.

These skills form the core tools you will use throughout this course. In the next lesson, you will study the planets in detail—their meanings, strengths, and roles in shaping a natal chart.

Assignment for Lesson 1 will be posted soon.